A friend’s blog post on being an Asian girl in a White world had me reflecting on how people like me (i.e., non-Asians) are treated here in Japan. As a white guy in an Asian world, it will come as no surprise that I get stared at. A lot. Everywhere I go, old people break their necks gawking at me, little kids lock their eyes on me like they’re about to launch laser-guided missiles, and everyone of every age in between stares wide-eyed and mouth agape as though they’d never seen a white guy before. (I write this recognizing that as a white, American man, I’m undoubtedly on top of the minority hierarchy here.)

I tell myself they can’t help but look. I consider myself of middling size and average features back home, but here I may as well be a giant space alien for how much I stand out. It’s only natural they’d stare. It’s instinctive. They’re not staring out of ill intent, I remind myself. But then again, maybe they are. Maybe that guy in the too-small suit is one of those right-wing loonies who holds a grudge against the United States for a war that happened long before he was born, or that old man giving me the stink eye thinks I’m yet another foreigner diluting the Japanese gene pool, or that group of snickering school girls caught me making a cultural faux pas that even a preschooler wouldn’t make. I don’t know what they’re all thinking. Who knows what anyone is thinking?

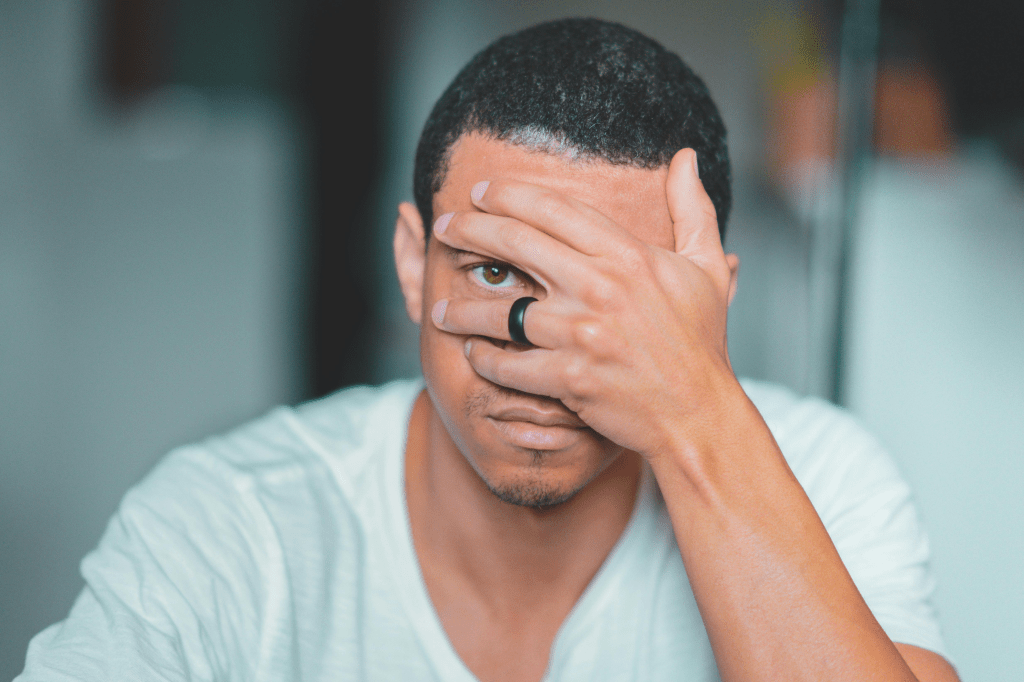

Staring isn’t benign. It may originate in curiosity, but to stare is to challenge, to draw attention to a perceived misgiving and set one’s will against another’s. There’s something animal in the response to being stared at, a gut instinct formed in our human ancestors long before language mediated actions. When I involuntarily think What the fuck you looking at?, I’m not using my evolutionarily-young frontal cortex to respond to their gaze—I’m an animal facing another animal ready to pounce.

I’ve tried several tactics in dealing with stares.

- The “Nani?” Approach. I say “What?” and throw back my chin. Result: They never respond and look at me confused/scared/about to call the cops.

- The Mirror Approach. I stare back at them, mirroring their gaze. Result: They avert their eyes and act like they totally weren’t just looking at me, or we both break our necks turning to look at each other in the most awkward staring contest ever.

- The Ignoring Approach. I pretend they’re not staring at me and let them look. Result: This is the most harmonious method. Though the stress of walking around with blinders, as though I were an animal in a zoo trying trick myself into thinking this is the savannah, is exhausting in its own right.

- The Hello! Approach. Say Hello! with the happiest, most stereotypical American attitude I can muster. Result: I can never say it without a heavy dose of sarcasm, and I end up being embarrassed by the rare, earnest hello I receive in return (reminding myself once again that sarcasm has yet to be invented here).

Regardless of which approach I take, I find being in public enervating and enraging.

Imagine this for a moment: no matter where you go—on the street, aboard a train or in your own car, in shops, restaurants, public restrooms, even atop the summit of a mountain—everyone you see either openly stares at you or has that look on their face that tells you they see you. You are seen. Everywhere and always. You are not like everyone else. You’re the Other.

(I tried embracing my otherness last summer by going for a shirtless bike ride. I figured that doing something that actually warrants a second glance would purge me of concern for all the day-to-day attention I receive. For while running or cycling shirtless in SoCal rarely elicits even a raised eyebrow, you may as well be buck naked without a shirt on in Japan. Most people even going swimming with shirts on. The experiment actually worked for a bit, creating a stare-proof armor on my psyche, but I wasn’t inclined to do it again after the feeling wore off.)

Even though I understand people’s reasons for staring, that it’s instinctive and not (necessarily) malicious, I can’t get past it. Is this what movie stars and incredibly attractive people feel like? Should I be flattered? I am an outsider here in Japan, no matter how good my Japanese becomes or how much I tie myself to this place, so perhaps it just comes with the territory. I should accept it and let it be. I shouldkeep it from getting to me. I shouldjust move on. Just as other people shouldn’tstare. I can’t change people’s actions and thoughts toward me nor how I instinctively respond to them, and I don’t know what to do with that.